Balancing conflicting human values for seagrass, saltmarsh and mangroves

- Posted by Chris Brown

- On July 25, 2020

The coast sits the intersection of many human activities. Management of coastal ecosystems is challenged by the conflicting values that humans hold for the coasts, including conservation, shipping, fishing, aquaculture, recreation and many others.

One objective of the Global Wetlands Project is to help find ways that management can balance these different values for coasts and secure conservation of coastal wetlands. In this post I’ll discuss some of the science we’ve completed so far on this topic and where we will go next.

Coastal wetlands are under intense pressure from activities that span multiple jurisdictions, in fact, they face more threats simultaneously than most other ocean ecosystems. These threats stem from human activities on land, such as agriculture that causes pollution, human carbon emissions that are causing climate change, and human activities in the ocean.

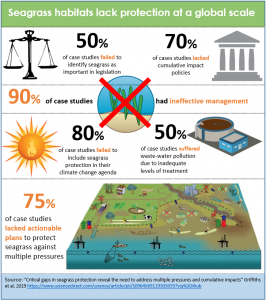

A detailed review of management in place for seagrass ecosystems found that management in most places only addressed a handful of the multitude of threats that seagrass meadows face. But, some examples of integrated plans that simultaneously dealt with multiple stressors show that it is possible to protect coastal wetlands, even in places of intense human pressures.

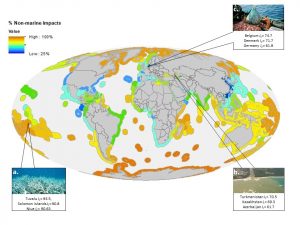

Addressing the three drivers of threat that coastal wetlands face – land, sea and climate – is complex, because the drivers operate at different scales, and so actions are needed across jurisdictions. We identified globally where there were mismatches between the actions needed to mitigate threats and the policies that are currently in place. For instance, the coastal zone of many nations is subject to high levels of human threats, but those nations are lacking management policies that cross the coastal zone.

Per cent of threats faced by ocean ecosystems that are caused by land-based or climate drivers. The prevalence of threats that are caused by climate change and human activities on land means action to conservation coastal ecosystems needs to span jurisdictions. Source: Tulloch et al. 2020 Biological Conservation

Mangrove ecosystems have some of the highest threat levels of any coastal ecosystem type. We studied associations between mangrove forest loss and the threats they face. Surprisingly, there was not a strong relationship between the rate of forest loss and the level of threat, at the global scale.

This may be because the threat data we used predicts the highest threats near urbanized areas. However, a key driver of mangrove loss is conversion of forest to shrimp ponds, which often occurs on rural coastlines. So while mangroves near cities may face high pressure from exploitation and future risks from development and ‘coastal squeeze’, forests on rural coastlines can also be subject to high rates of loss.

We also found that protected areas had lower rates of mangrove loss, but only in countries that had overall poorer capacity to manage environmental protections. This counter-intuitive result makes sense when you consider that mangroves are often protected outside of parks too, such as by fish habitat legislation. Therefore it seems that countries with good capacity to enforce protections can protect mangroves everywhere, whereas parks are important in countries that have more limited capacity to manage forests.

Overall the study highlights the importance of having region specific management actions to address mangrove loss.

Our next steps are to apply these methodologies that we’ve developed for studying threats, trends and management of coastal wetlands to all coastal wetland habitat types. This will form the basis of our global-scale, but regionally relevant, index of the status of coastal wetlands.

0 Comments