Transforming multiple stressor science to enhance coastal wetland protection

- Posted by Kai Ching Cheong

- On November 30, 2022

By Andria Ostrowski

Stressors rarely remain static in the environment, yet we continue to conduct multi-stressor experiments under highly controlled conditions, keeping stressors constant over time. So, what happens when stressors fluctuate? This is the question we explored in our new study, published in Ecology Letters. We found that how stressors are introduced elicits different biological responses in seagrasses.

Seagrasses provide critical habitat for wildlife, from shrimp to sea turtles and dugongs. These marine plants also stabilise sediments, store carbon, protect coastlines, and improve coastal water quality.

Despite widespread benefits, seagrasses are disappearing globally. Human activities play a major role in this loss by introducing multiple co-occurring stressors to the environment, such as pollutants, physical disturbance, and increasing temperatures. This means that seagrasses can be simultaneously affected by two or more stressors.

Seagrass ecosystems provide services that are of ecological and economic importance, yet they continue to face immense threats from human pressures worldwide.

It is critical to understand how these multiple stressors interact to impact seagrass habitats so that we can better manage adverse effects. We derive this understanding from experiments conducted in the lab or field. Typically, we test for the effects of multiple stressors under highly controlled, static conditions, where stressor intensity stays constant throughout the experiment. However, this ignores dynamic environmental changes that occur in coastal ecosystems.

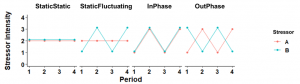

We evaluated the effects of changes in stressor intensity (i.e., fluctuations) and synchronicity (i.e., timing of fluctuations) on seagrass responses to reduced light conditions paired with herbicide contamination. We compared responses to those observed when both stressors remained static over time – the current ‘standard’ method used in multiple stressor experiments.

Variations in stressor intensity and synchronicity tested, including (from left to right): static-static, static-fluctuating or fluctuating-static, synchronous (in-phase), and asynchronous (out-phase) fluctuations.

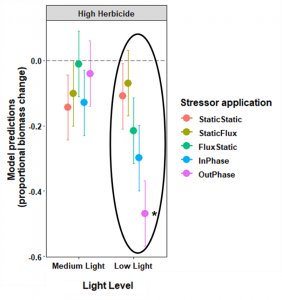

Under high-intensity stressor treatments, asynchronous fluctuations reduced seagrass biomass 36% more than those exposed to static stressor conditions. And this difference was found despite all treatments being exposed to the same average level of stress.

Our results provide evidence that there are differences in biological responses dependent on how stressors are introduced to the environment. A finding that suggests conclusions drawn from past research might not provide a comprehensive understanding of multiple stressor effects in the real world.

High-intensity, asynchronous (i.e., out-phase) stressor fluctuations had a greater impact on seagrass biomass reduction compared to static stressors, but only under the most stressed conditions.

We propose that future multiple stressor experiments incorporate environmentally relevant changes in stressor intensity and synchronicity. Adopting this approach may provide more accurate information of multiple stressor effects that can aid in the development of better conservation and management strategies, not only for seagrass, but for all ecosystems.

0 Comments