Multiple stressors in coastal wetlands: shifting our focus to real world scenarios

- Posted by Marina Richardson

- On January 20, 2021

By Andria Ostrowski

Vegetated coastal wetlands including saltmarshes, mangrove forests and seagrass meadows store large amounts of carbon, protect shorelines from storms and erosion, support enormous biodiversity and improve water quality by filtering nutrients, contaminants and sediments.

Despite their ecological and economic importance, increasing human settlement and development along coastlines introduce stressors that affect coastal wetlands. These stressors, such as excess nutrients, pollutants and climate change, often co-occur within the environment, resulting in complex and often disastrous impacts to ecosystem structure and function.

Coastal wetlands – seagrasses, mangroves and saltmarshes – are faced with a range of human stressors, which often affect these habitats at the same time.

To help alleviate these impacts, we need to research how multiple stressors affect these habitats, and we need to conduct this research efficiently and effectively…but are we?

To answer this question, we reviewed multiple stressor studies to investigate how they are designed and conducted within saltmarsh, mangrove and seagrass ecosystems. Research on multiple stressors is growing rapidly and excellent experiments have been conducted all around the world, helping to guide management of coastal habitats.

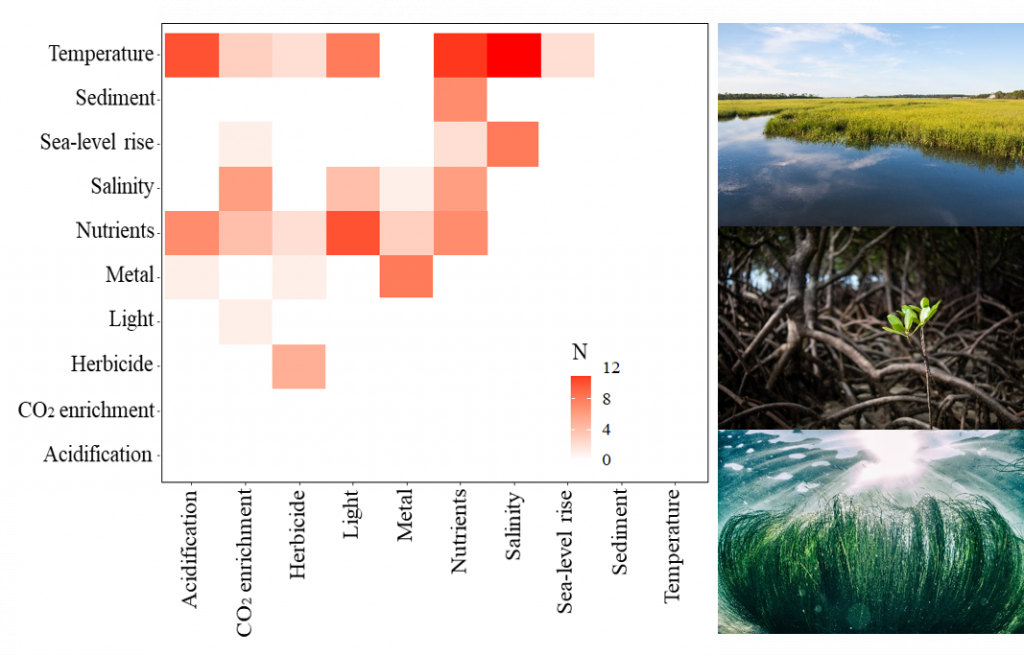

Number of multiple stressor studies that investigated the effects of various stressor combinations in saltmarsh, mangrove and seagrass ecosystems.

We found the effects of increased temperature and nutrient input were studied most often. The most common stressor pairing investigated across the three ecosystems was the combined effects of increased temperature and salinity.

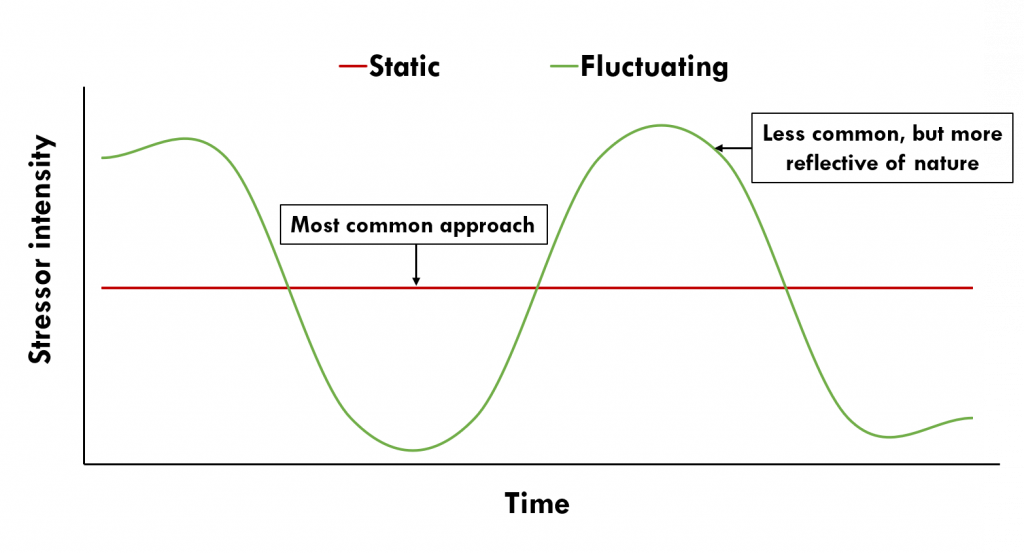

However, we also found an interesting and concerning trend. Almost all studies were conducted under highly controlled conditions that exclude natural variation. Stressors may rarely remain at ‘static’ (or constant) levels throughout time, yet this is how we often introduce stressors in experiments. But since coastal wetlands are highly dynamic, environmental conditions are in a constant state of change. For example, tidal cycles and rainfall patterns mean that exposure to stressors can vary considerably throughout the day.

As conditions within coastal wetlands change, stressor intensity is likely to fluctuate over time. However, we rarely incorporate changes in stressor intensity in experiments. Rather, we introduce stressors statically.

As conditions within coastal wetlands change, stressor intensity is likely to fluctuate over time. However, we rarely incorporate changes in stressor intensity in experiments. Rather, we introduce stressors statically.

This key finding suggests that the most common ways we conduct multiple stressor research may be providing misleading information about how stressors affect real world ecosystems.

Therefore, we show that it is important to incorporate more realistic experimental design in multiple stressor studies that reflect natural environmental conditions.

We provide the following recommendations to enhance realism:

- Vary stressor intensity and timing to reflect natural variability within coastal environments.

- Conduct long-term studies to investigate how stressors and their effects change over time.

- Where practical, conduct field studies alongside lab experiments to investigate how effects differ in natural environments.

- Evaluate the effects of stressor pairings not yet studied.

Designing multiple stressor experiments that are more representative of nature will enhance our understanding of how stressors impact coastal wetlands. Evaluating how environmental variability influences stressors is also key for improved conservation and management of coastal wetlands.

0 Comments