Predicting carbon emissions from mangrove loss to count progress on climate change

- Posted by Natasha Watson

- On April 6, 2021

Mangroves are a blue carbon ecosystem and have among the highest carbon densities of any tropical forest. In a new study we show how action to prevent mangrove loss can contribute to reducing future greenhouse gas emission.

Under the Paris Climate Agreement, nations need to show how they intend to reduce carbon emissions. Protection of mangroves is an important climate action, because mangroves accumulate three to ten times more carbon than most ecosystems on the planet. But actions for reducing emissions by reducing loss of mangrove forests can be contentious. We need to know what a nation would have emitted without new actions to protection mangroves against what it is projected to emit if no action is taken. In our study, we projected for the first time global carbon emissions from different drivers of mangrove deforestation.

You can explore projections for nations in our new web application: https://mangrove-carbon.wetlands.app/

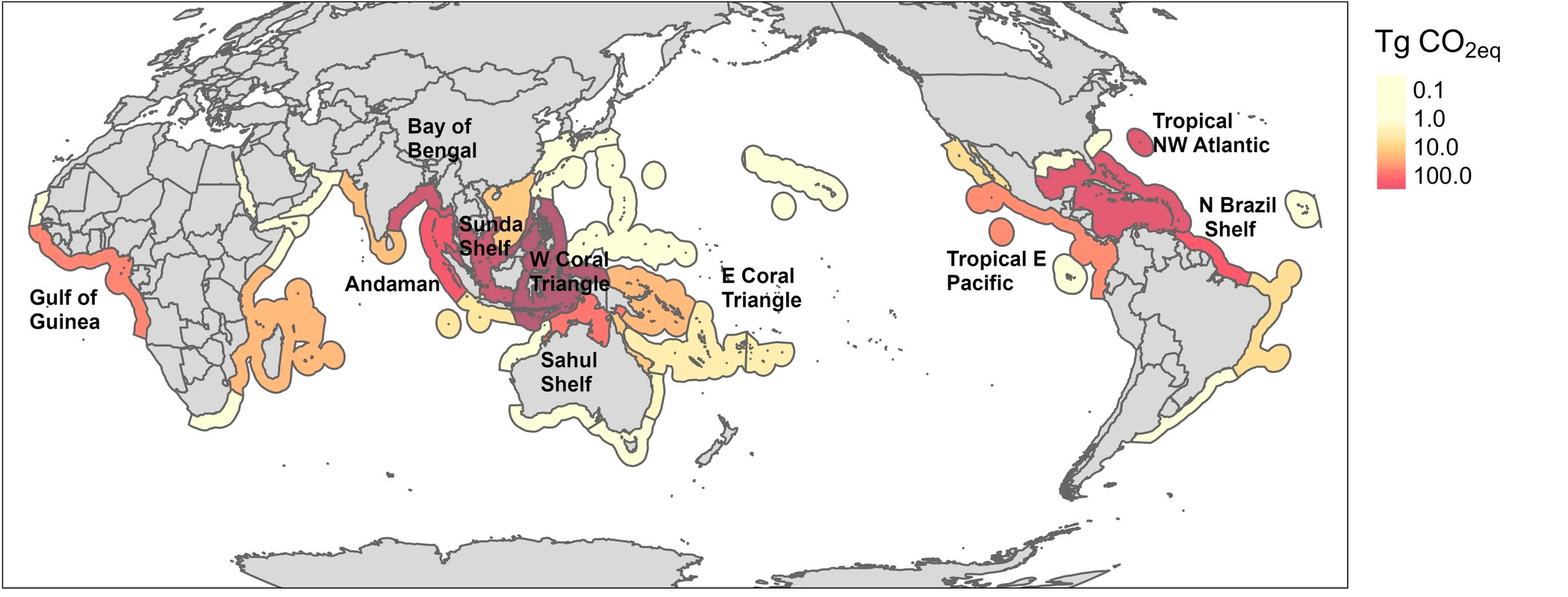

We looked at five key drivers of carbon emissions from mangrove loss: clearing of the coast, urbanisation, aquaculture and agriculture, erosion and extreme climatic events. There is much variation across the world both in the amount of emissions projected and the causes of those emissions.

Image: Projections of carbon emissions (Terragrams of CO2 equivalent), figure from Adame et al. 2021.

Image: Projections of carbon emissions (Terragrams of CO2 equivalent), figure from Adame et al. 2021.

For example, Australia is doing relatively well compared to other regions of the world, but extreme climate events are a major cause of emissions here.

Overseas, emissions from mangrove loss are concentrated in five regions of the world; which are also global hotspots of rising carbon emissions: southeast and south Asia due to agriculture and aquaculture, and the Caribbean, west Myanmar and North Brazil due to erosion and clearing.

These projections help nations value mangrove conservation, identify what actions are needed to reduce emissions and set targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The Indonesian government, for example, has recently declared a moratorium on clearing mangroves for shrimp farms. Our projects could be used to inform on how much carbon emissions that moratorium could save.

Our study advances earlier studies on blue carbon by making predictions of carbon emissions for the future. There are many earlier studies of the global scale potential of mangroves to capture and store blue carbon. But, these studies are historical accounts of what is there and what has been lost.

Climate agreements, like the Paris agreement, require future projections that governments can use as baselines to set actions for reducing emissions and capturing carbon. Our study provides those predictions.

This advance was made possible by the availability of global-scale mangrove datasets and international collaboration. At the Global Wetlands Project, researchers who are experts in blue carbon, spatial analysis and modelling collaborated with national and international mangrove experts.

We first pulled together several large global datasets that were developed by different teams. These datasets included maps of the distribution of mangrove, mangrove carbon storage and causes of mangrove deforestation.

We then used this data to inform our models that project carbon emissions. This enabled us to make predictions of all of the world’s mangrove regions.

We also made several advances through the modelling. Our earlier modelling work had modelled just the emissions caused when mangroves are lost. But, mangroves also capture carbon as they grow. So the loss of mangroves represents a lost opportunity to capture carbon. In this new modelling we accounted for that lost opportunity.

Second, we conducted a rigourous analysis of our ability to accurately predict emissions. We found that the projected rates of mangrove deforestation are the main source of differences in emissions, with large changes in the projections depending on what future rates of loss we assumed.

This is good news for mangrove conservation, because it means that action to reduce deforestation can have a large impact on emissions.

There were also some differences in projections when we used different global maps of the distribution of mangroves. These maps represent different mapping methods, and none are perfect. But importantly, the locations of the hotspots of emissions did not depend on what map we used.

Therefore, we can be certain that south-east Asia, the Caribbean and north Brazil are the most likely hotspots of future carbon emissions.

In future work we will be applying these methods at smaller scales to inform regional management and conservation policy for mangroves.

For more information see Adame et al. 2021, Future carbon emissions from global mangrove forest loss, Global Change Biology.

0 Comments